Introduction

Algeria’s economic policies in the last 20 years have contributed to Algerians’ low standard of living, in spite of the relative financial security known to the public treasury. The failure of economic policies and the spread of administrative corruption contributed to the deteriorating purchasing power of social groups living in poverty, including low-income workers. The Algerian government added new tax burdens on consumer goods, especially after the decline in oil prices. The neoliberal policies pursued by the regime of former Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika contributed to the penetration of corrupt money between the wheels of management and dominance by employers’ organisations.

Algeria has known waves of protests demanding economic reform over the past years, but soon these protests took their political shape in 2014 against the fourth term extension of former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika and until 2019 when protesters demanded that Bouteflika doesn’t run for a fifth term. This was the most important demand ever. The wave of protests started from the city of Khenchela in the country’s east, which was led by a group of unemployed youth only to spread from there to other cities. These protests contributed to thwarting Bouteflika’s candidacy for a fifth term and the halting of the 2019 presidential elections. This article seeks to determine the role and position of trade union organisations in the recent protests.

Historical roles for the unions

Union and labor movements in Algeria have played the central role and the main driver of the protests in the past twenty years, resisting the consequences of the tight economic policies and the neoliberal policies in place. This, in turn, has pushed for a tense relationship between unions and successive governments. In addition to unions, unstructured social groups, such as workers, the unemployed and marginalised groups, have played a role in recent protests as well. The pivotal role of labor and trade union movements has made them a subject of interest and polarisation from all actors in society, including political parties, the government, political security services, and international organisations.

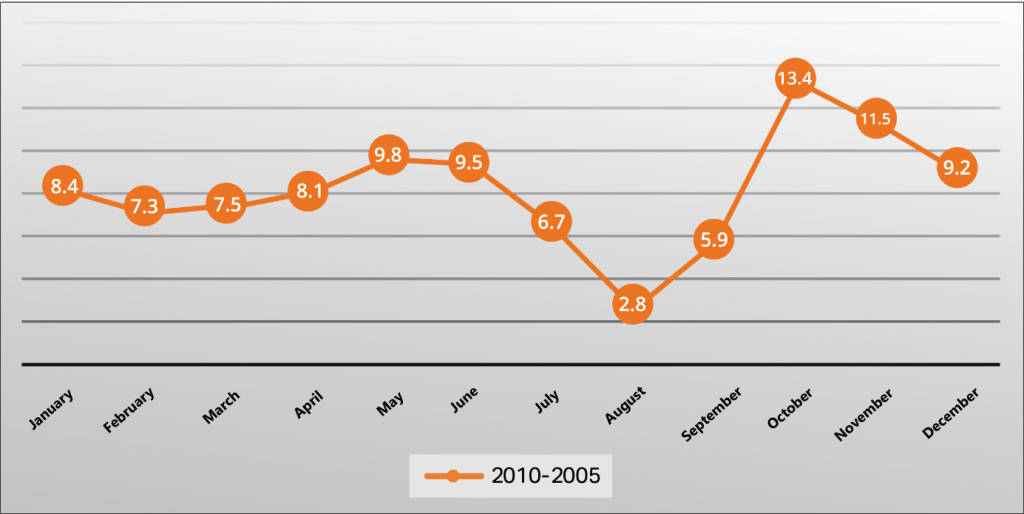

The number of strike days organised by unions in the years between 2005 and 2010 reached 1,142 days; that is, almost three years of strike in a period of five years.

The unions in Algeria have struggled to maintain their material independence and to voice out their criticisms. However, this independence was the subject of long and deep compromise. There have been real attempts to domesticate trade union activity and to divert their course from its primary goal. Therefore, unions in Algeria utilised defensive tactics in their relationship with the government. In many cases, the regime managed to exert pressure on some trade unions in one way or another, weakening their activity by creating internal splits, and by denying them permits for carrying out their activities.[1]

The growing interest in the role of unions is due to their organisational ability to mobilise and frame, and equally for their contributions to raising the working groups’ awareness of their social and political situation. The number of strike days organised by unions in the years between 2005 and 2010 reached 1,142 days; that is, almost three years of strike in a period of five years.[2]

The protest union activity witnessed a change in terms of actors and sectors. Union activity has shifted to the public job sector after it was limited to the industrial sector. The Algerian union activity first focused on blue-collar jobs, such as factory workers, and then shifted to white-collar jobs, such as doctors, teachers and public sector employees. The expansion of protest union categories contributed to the expansion of the geographical span of protests and increased the number of participants.

Labor and trade union movements and the journey to find roles within the movement

What distinguishes the Algerian union movement is that the participating social groups’ sub-identities are absorbed into a dominant and prevailing identity, which was built on the basis of opposition and resistance to the policies of the existing authority. It was not possible for those looking from afar to feel the distinction between the professional and labor groups, except through some slogans specific to certain professions that were raised by workers of energy and gas institutions, civil defense workers, teachers, doctors, lawyers and judges.

The unions have maintained their defensive techniques by using their sources of strength as a strategic choice when dealing with the authorities. Among these strategies are the unions’ preference for the “social entry” period to intensify their strikes. To clarify, the period of “social entry” is the period of September, October and November of each year, and it is considered a preference period because they can exert pressure on the government while meetings between the government, the organisation of Algerian employers, and the General Union of Algerian Workers, the single representative body of Algerian workers. In the meetings, economic and social policies vis-a-vis workers are discussed, and decisive decisions regarding wages are taken. The “social entry” period is also the period when workers join their work after the holidays, and therefore, any strike that would take place should create enormous pressure on the government. Unions use the “social entry” period as a strategic option to ensure their demands are met, including their inclusion in the social dialogue and their recognition as a social partner.

Chart No. 1: Distribution of the percentage of independent unions’ strikes by month in the period between 2005 to 2010[3]

Unions in Algeria participated in various coordination meetings with civil society organisations and political parties, the most important of which was the “Dialogue Forum” and which was held on the 6th of last July in “Ain al-Bunyan” in the capital, Algiers, to discuss ways to deal with issues related to the representation of the union movement, define its demands and confront the policy of the authorities toward the movement.

Trade unions also organised labor gatherings in a number of provinces, especially in the industrial regions, such as Oran in the western part of the country as well as Bejaia, Tizi-Ouzou, Annaba and Bordj Bou Arréridj in the east of the country. These gatherings called for the release of detainees in prison due to the protests. In the same context, Massoud Boudibah, a spokesman for the “national council of higher education”, which is the largest trade union organisation in the education sector in Algeria, said the workers’ protest movement comes in the context of taking a position in support of the demands of the Algerian people, raised since February 2019. Boudibah also reiterated the importance of this movement as it rejected attempts to circumvent protesters’ legitimate demands, by imposing a solution path that does not respect the majority of Algerians, pointing to many of the demands regarding political participation and public freedoms.

Independent unions in Algeria announced a general strike on October 29, 2019, and organised rallies in various regions, as a means of exerting pressure on the regime, which intended to organise the presidential elections on December 12, 2019.

Looking at the Algerian protest movement, one can discern the serious attempts of the unions in seeking legitimacy, which pushed trade union organisations to hunker behind the demands movement and to identify with peaceful protests despite the lack of agreement on their demands. However, the momentum of the protests represented trade unions with an opportunity that they can utilise, and therefore work to raise unionistic and professional demands using political means.

The Algerian trade union confederation ‒ a gathering of most trade unions, including health, education and public service sectors ‒ supported the popular movement in order to pressure the authorities to stop the arrest campaign against activists, to remove Noureddine Badawi’s government, to withdraw the draft Hydrocarbon Law, to restore workers’ right to relative retirement and their right to retirement without age restrictions, and to protest the high prices and the decline in purchasing power.

Conclusion

The unions’ organisational and mobilising advantage did not allow them a special place in the recent movement in Algeria, due to various reasons, perhaps the most important of which is the defensive techniques they adopted in their relationship with the authorities. This approach, which the unions have long resorted to, is motivated by their desire to not sever the relationship with the authorities and to be recognised as a partner in social dialogue. Unions have relied on strategic and rational readings in their dealings with the government, which negatively affected their position in the movement, as unions are seeking legitimacy in a new era.

Before the recent protests, the Algerian unions were fighting a struggle for social justice and the defense of the working classes. Now they are facing a challenge of the importance of having concrete political and economic perceptions, and maintaining a minimum of their organisational capacity, without falling under the guardianship or influences around them.

[1] Hussein Zubairi, “The Challenges of the New or Independent Trade Union Movement in Egypt and Algeria”, Democracy Volume 15, Issue 59 (2015), pp. 58-71. Available only in Arabic.

[2] Hussein Zubairi. Sociology of the Union Movement in Algeria: Legacy of the Past and Strategies of the Present. (Algeria, The Dome: Khaldunia House for Publishing and Distribution, 2019). Available only in Arabic.

[3] Hussein Zubairi. Sociology of the Union Movement in Algeria: Legacy of the Past and Strategies of the Present. (Algeria, The Dome: Khaldunia House for Publishing and Distribution, 2019). P. 150. Available only in Arabic.

Visto International bears no responsibility for the content of the articles published on its website. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Organisation. All writers are encouraged to freely and openly exchange their views and enrich existing debates based on mutual respect.