COVID-19 in the Palestinian territories: challenges and solutions

The Palestinian Territories recorded the first 7 cases of the novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) on March 5, 2020. On the same day, the Palestinian Government announced a state of emergency for 30 days, which was then extended for another month by a presidential decree in early April 2020. A ban on movement between governorates and within cities was also announced almost two weeks later as the number of cases continued to rise. Essential travel was made an exception, and only in relation to healthcare, security and the provision of food, also subject to certain restrictions.

The crisis raised many concerns, the most prominent of which was the extent to which the Palestinian territories are equipped and prepared to withstand the repercussions of the unfolding crisis, and to properly deal with it. It also highlighted some of the most pertinent challenges that could impede the Palestinian Authority’s plans to confront the pandemic.

Thematic challenges

While the Palestinian Authority is now managing a crisis on geographically fragmented lands, it is doing so with a usurped political sovereignty. This is the result of the Oslo agreement signed between the PLO and Israel, as well as the nature of the Israeli measures that followed the second Palestinian intifada (or uprising) in 2000.

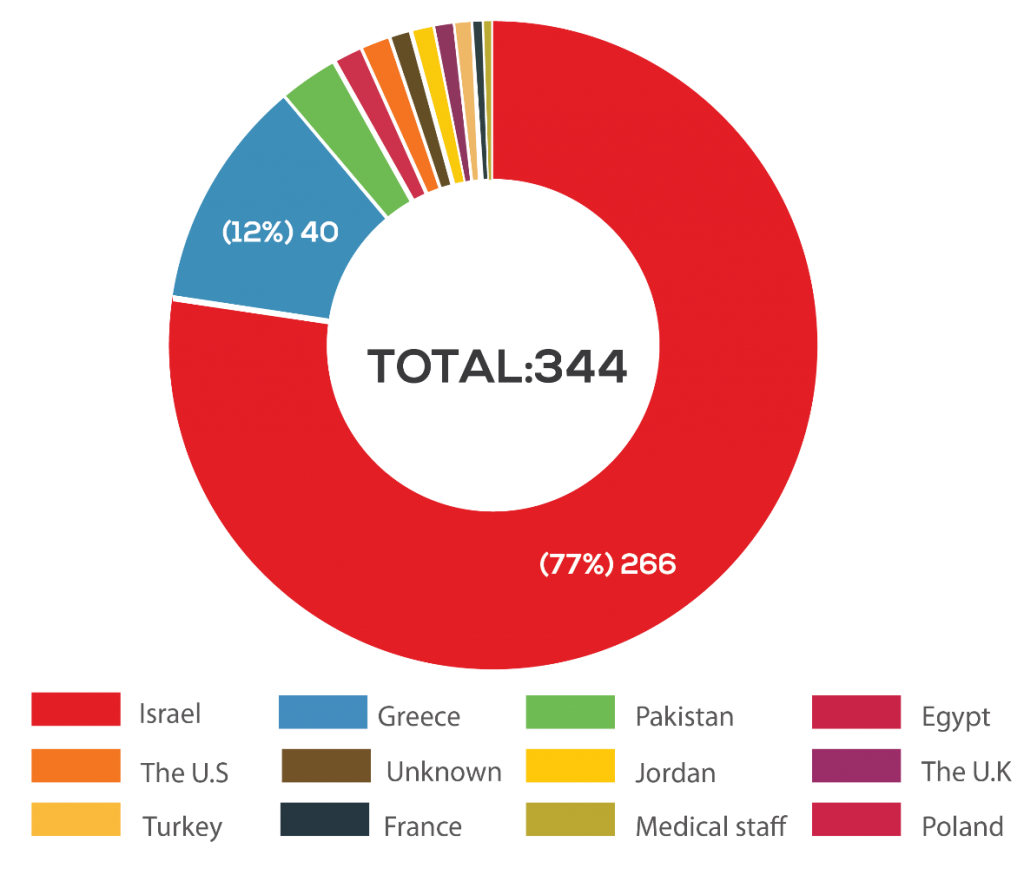

The Israeli imposed reality is the greatest challenge to the Palestinian Authority, as Israel controls all land, sea and air routes. The illegal settlements are spread over vast areas of Palestinian lands, while Palestinian workers in these settlements are facing the risk of Covid-19 transmission. In fact, statistics by the Palestinian Ministry of Health show that about 76% of Palestinians who contracted the virus are either workers in the occupied territories or people who have been in contact with them.

Distribution of sources of COVID-19 cases in the Palestinian territories

While facing the crisis, Israel rejects any PA action in East Jerusalem and ‘Area C’ of the West Bank. Instead, Israel works to restrict the movements of Palestinian officials working to combat the virus. An example of this is the arrest of the Minister and governor of East Jerusalem.

The health situation

According to data published by the Palestinian Ministry of Health, the number of infections since the beginning of the crisis in early March until the 26th of April has reached 495 cases. In fact, 251 of them were from East Jerusalem, and 17 from the Gaza Strip. In addition to a number of infections among the Palestinian diaspora, the rest of the infections are distributed across the governorates of the West Bank.

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Health, the number of ventilators available is 120, and it is possible to increase them by another 250, provided in aid. This means that if the crisis widens and the number of infected people in need of ventilation increases, the PA will be facing an acute shortage of supplies. This challenge is compounded by the lack of sufficient numbers of test kits. The result is that the PA can only test a few hundreds per day. The shortage in medical staff and the lack of places for isolating suspected and confirmed cases are both additional challenges to the PA’s ability to respond to the crisis. Statistics by the Ministry of Health again show that since the beginning of the crisis until April 25, a total of only about 29,000 tests have been conducted. These are some of the indicators of a weak health infrastructure, and they will be hard to address in the foreseeable future. This is causing fear that the crisis may become too difficult to manage if the virus continues to spread on a wider scale.

The economic challenge

In 2019, the Palestinian economy relied heavily on taxes, customs, and fees paid by citizens and local institutions. It represents 95% of the Palestinian Authority’s resources. As a result of the state of emergency and stagnation, financial revenues may well decline by 50 percent. This has forced the PA to cut salaries of its civil servants.

According to Palestinian Prime Minister Dr. Muhammad Shtayeh, the deficit in the Palestinian budget has reached about $1.4 billion, while international and local reports estimate that about the Palestinian economy and its GDP will shrink by 20% until the end of the year, which is equivalent to $3.2 billion in losses.

As for poor families, the government added some 11,000 new families to the list of recipients of government financial assistance during last April, and will add another 9,000 families in the next month, bringing the total number to 125,000 families receiving financial assistance, the majority of which reside in the Gaza Strip.

In order to deal with the economic aspect of the pandemic, the government has taken a number of steps. The Palestinian Authority announced that it will provide $300 million as loans for small and medium enterprises affected by the crisis.

The Palestinian Authority announced the creation of a fund called “Waqfet Izz” (literally, a stand for dignity) to contribute to coping with the crisis in Palestine. The campaign aims to collect 20 million Jordanian dinars (28 million dollars). However, a total of only 8 million dinars ($11 million) was collected as of April 27.

The internal divide and crisis management

Since June 2007 until now, the Palestinian political system suffers from the internal Palestinian divide, which led to the formation of two authorities, one in the West Bank, and the other in the Gaza Strip. Regardless of the factors that led to this situation, the divide has had its effects on the management of the crisis.

Perhaps most visible was the lack of a unified briefing of the health situation by the ministry of health in both territories. Adding to the confusion, two press conferences would be held at different times in both Gaza and the West Bank, separately giving updates on the latest developments regarding the crisis.

There was no coordination in the administrative steps and decisions taken to avoid the effects of the pandemic. At a time when Ramallah announced decisions to suspend schools, universities and many sectors, Gaza did not take the same measures and worked according to its own vision.

The current situation led to several parties calling for an end to the internal division, which may contribute to the development of unified plans to confront the pandemic.

Conclusion: weathering the crisis

Until the moment, the Palestinian Authority’s early declaration of a state of emergency as well as the ensuing intra- and inter-governorate restrictions on movement may be the best options available to face the pandemic. If we take a close look at the nature of the current challenges, certain factors need to be considered to ensure an effective response, including:

First, both the official authorities and the general public need to cooperate with each other with the aim of becoming fully aware of how to deal with the pandemic by means of prevention.

Second, the relationship between the different components of Palestinian society needs to be reshaped. That is, all stakeholders need to take a unified stance, not only in relation to facing the crisis, but also in regard to rebuilding and developing society in light of the expected repercussions of this crisis.

Third, a national committee that includes the Palestinian political, social, and economic actors should be formed. The relevant economic and development plans need to be laid out to withstand the impact of the crisis.

Visto International bears no responsibility for the content of the articles published on its website. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Organisation. All writers are encouraged to freely and openly exchange their views and enrich existing debates based on mutual respect.