Women participation in STEM Majors and Scientific research: realities and challenges

In 2015, the United Nations signed the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which includes seventeen goals known as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The fifth goal is gender equality, which aims to empower all women and girls, and to ensure equal access to equal opportunities in education, work as well as political and social representation for both genders. Although several countries have allocated budgets to ensure the implementation of this goal across most areas of life, women’s representation is still far from equal, including their participation in areas and research in the natural sciences.

So, how are gender differences accounted for in scientific areas? How do social factors affect women’s involvement in areas of science that continue to be branded as ‘masculine fields’ or ‘man’s domain’?

Statistics on women’s participation in scientific research

A 2014 study published by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the United States of America showed that the proportion of talented females exceeded half of the overall number of students for that year.

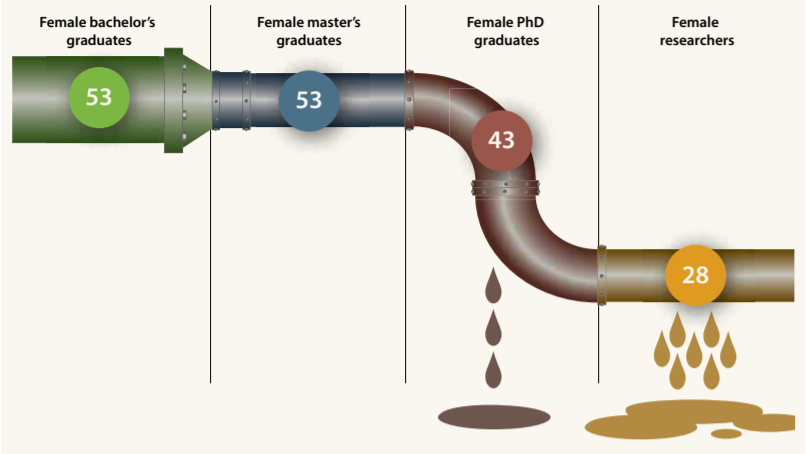

The declining rate of women participating in scientific research is the result of what studies call ‘pipeline leakage’. Female graduates who don’t end up as researchers in their respective fields are called ‘leaky pipeliners’.

There’s a clear rise in the number of female undergraduates from Biomedical and Medical Sciences as well as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (or STEM) fields in the U.S. In 2017, 50% of students holding a Bachelor’s degree in engineering were female, while 44% were male. However, once these females have graduated, their participation in scientific research declines. UNESCO has published a report showing that female researchers in biological sciences make up only 30% of students, a low percent that does not measure up to the United Nations goal to raise female representation in various areas of life.

Regarding the number of female students pursuing graduate studies in STEM majors, the data shows a sharp decline in the number of female students at both Master’s and PhD levels. For instance, only 28.5% of PhD graduates in Mathematics are females, while female PhD graduates in IT make up only 32.2%. The number for female PhD graduates in computer science is even less, accounting for only 20.1% of all students. This decline has prompted many researchers to propose explanations and study the reasons behind this phenomena.

Source: UNISCO institute for statistics. July 2015

The variability hypothesis as an interpretive framework

Several explanations have been offered to account for male versus female participation in scientific studies and research. The most important of such explanations is the ‘variability hypothesis’, also known as the ‘greater male variability’.[1] The hypothesis holds that males display greater individual variability than females in physical and psychological characteristics. This variability, the hypothesis indicates, makes males likely to surpass females in scientific excellence.

Recent studies[2] criticised the variability hypothesis in that it is too limited to account for the many factors that should be considered to favor one gender over the other in certain areas. New studies and reports show that educational achievement among females is higher than among males. In addition, females on average scored slightly higher than males in scientific disciplines, as shown in the diagram below.

Other explanations discuss the proportion of women participating in scientific research. Some of these refer to the fact that females need more emotional support than males so they can feel motivated to carry out scientific research. This is called the “growth mindset”. That is, women are more affected by negative feedback than their male counterparts.[3] Female students whose parents and professors continue to remind them that their intelligence will expand more with experience and learning are more likely to have higher scores in math and science tests than their unmotivated counterparts.

Female students whose parents and professors continue to remind them that their intelligence will expand more with experience and learning are more likely to have higher scores in math and science tests than their unmotivated counterparts.

This also applies to motivating women to complete their university studies in scientific disciplines, especially in environments where stereotypes prevail about females being unable to match their male peers in scientific disciplines. In a math test made as part of a 2008 study, female students who were told that genes had no effect on performance scored higher than their peers who were told genes are an essential determining factor.[4] This shows that female self-confidence prompts them to choose majors that are stereotypically challenging, which helps bridge the gap between the representation of women and men in areas of scientific research.

The challenge of family-work balancing is another explanation to be added to the two previous ones. This is also known as women’s “social role”. Women’s ability to pursue their graduate education, to establish a professional research career and to develop their skills are usually entangled by their socially inscribed commitment towards the family-expected duties. The better women are able to strike a balance between family and work lives, the better their progress in scientific research. In addition, women’s role at work should be restricted to certain parameters so as not to contradict her obligations to her family.[5]

Local policies and their impact on women’s participation in scientific study and research

The number of women participating in scientific fields varies from one region to another, amounting to 52% in the Philippines and Thailand, while also reaching equality in Malaysia, for instance. This is believed to be due to government support to empower women and allow them access to education. This is evident in the rate of women’s participation in education increasing 36 times between 1957 and 2000, according to the United Nations Development Program. In Turkey, one out of every three researchers is a female; i.e. female researchers make up 36% of all researchers. In the Arab world, about 39% of researchers are female, while country-to-country variation still exists. The Sultanate of Oman boasts 70% female researchers, followed by Egypt at 44%, then Sudan and Iraq increasing by 40%, while Palestine and Saudi Arabia retreated by 23%.

Female participation in scientific research is still low despite the efforts of the United Nations and many countries to bridge the gap and achieve gender parity in all fields

In its “UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030”, the organisation attributes the large gap between the high percentage of female graduates from higher education in the Arab world and the small percentage of female participants in scientific research and employment in scientific fields to intertwined social, cultural and economic factors. Strong determinants include: the societal environment, restrictions on the movement and travel of girls for study, the family’s economic situation, government support for girls, and the societal view of the role of women in the family.

To conclude, female participation in scientific research is still low despite the efforts of the United Nations and many countries to bridge the gap and achieve gender parity in all fields. This should lead us to stress the importance of the legal legislations concerned with imposing laws that guarantee equality in science and work. It should also encourage support for women through budgetary commitments by the state and the private sector to help them achieve scientific progress alongside their societal responsibilities. Relevant programs should be implemented to help both genders qualify in order to establish more equality and parity the United Nations is aspiring to achieve as part of its 2030 vision.

[1] Ellis, H. (1894). Man and woman: A study of human sexual characters. London: Heinemann. 1934.

[2] O’Dea, RE, Lagisz, M., Jennions, MD et al. Gender differences in individual variation in academic grades fail to fit expected patterns for STEM. Nat Commun 9, 3777 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06292-0

[3] Adriana D. Kugler, Catherine H. Tinsley, Olga Ukhaneva. Choice Of Majors: Are Women Really Different From Men ?. Cambridge, MA. August 2017.

[4] Carol S. Dweck. Mindsets and Math / Science Achievement. Stanford University, CA. 2008

[5] Jean, VA, Payne, SC, & Thompson, RJ (2015). Women in STEM: Family-related challenges and initiatives. In M. Mills (Ed.), Gender and the work-family experience: An intersection of two domains (pp. 291-311). New York: Springer.

Visto International bears no responsibility for the content of the articles published on its website. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Organisation. All writers are encouraged to freely and openly exchange their views and enrich existing debates based on mutual respect.